By this measure, NAPPS, the OIDF WG chartered to define mechanisms in support of an SSO experience for native applications, is an awesome standards effort.

As has been previously pointed out by John Bradley and myself, the mobile OSs are evolving their support for native SSO, both iOS and Android are adding new features that make SSO possible 'out of the box', without the introduction of specialized application software on the device, as the NAPPS group had been proposing. Consequently, the value of the 'Token Agent' model that NAPPS was proposing and standardizing is diminished - fundamentally we don't need to supplement the mobile OSs to achieve native SSO when they provide sufficient capabilities on their own.

Consequently, as John writes, the NAPPS WG is 'pivoting' and, rather than delivering a normative specification for the Token Agent role, will instead:

"...document best

practices for Single Sign-on for Enterprise and Software as a Service

Providers using these new features in combination with the PKCE

specification, as well as filling in any remaining gaps to allow SaaS

providers to fully support OAuth and OpenID Connect enabled native

applications in a secure way without forcing users into extra

unproductive logins."

In addition to these sort of guidelines, there is discussion about the development of open source SDKs that would wrap up all these features and flows - simplifying for application developers how to hook into this native SSO model. Discussions are underway as to where development of these libraries make sense.

Interestingly, while the value of a Token Agent has been marginalized by the new mobile OS features for the native SSO use case, the TA model may yet find a home in the Internet of Things.

Many IoT devices are characterized by limited UI capabilities for display and user input - both of which are critical for the initial binding of the device to a user account and corresponding provisioning of credentials. But if Things are constrained in this way, mobile devices aren't - and so can facilitate this initial setup step.

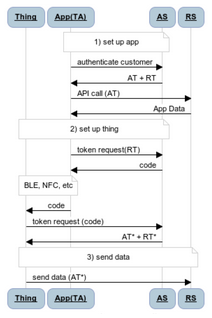

Shown here is a scenario where a native application on a device plays the role of a Token Agent on behalf of a Thing. The TA obtains an OAuth access token for the Thing and then delivers that token using some short range wireless protocol such as BLE or NFC. Once the Thing has its token, it can use that to authenticate itself when interacting with cloud endpoints or even other Things.

Should the TA model be eventually applied to IoT use cases, perhaps my not insignificant $$ investment in a large supply of 'There is nothing token about my agent' t-shirts will not be wasted. Let us hope.